- The Oxford Companion to French Literature has this to say about Les Miserables: 'The book is made still more unwieldy by the continual insertion of long historical, political, or sociological dissertations. Interesting ones are the description of the battle of Waterloo, the study of the end of the Restoration period and the figure of Louis-Philippe, the famous description of the Paris sewers, and numerous pictures of Paris and Parisian underworld life.'

To readers expecting only a clear character-driven narrative, these diversions are indeed unorthodox left turns that "don't move the plot forward." Let's call that "plot" part, the part where we are meant to wonder what is going to happen to a major character, The Drama. There are a whole lot of digressions that seem independent from The Drama, and these digressions usually go on for a bit. In fact, they take up 25% of the book. What are we to make of them? Some possibilities follow.

I have my own theory about the diversions in LES MISERABLES: they are there for the patient, and they are there for a reason. The first time you read the novel, they do indeed make the book feel unwieldy. They throw you for a loop. To use an archaic, sexist saying, they separate the men from the boys within the reader base. Wimps may proceed to the abridged edition. The second time through, though, you pick up thematic connections that you couldn't possibly have picked up the first time. And the book draws you in deeper as a result.

For instance, the long bit about Waterloo culminates in some musings on destiny that are somehow more relevant once you have taken in the whole story. A lengthy lecture on the nature of human progress means more once you realize it really is there for a reason -- Hugo is about to introduce four vicious career criminals. And the extended tour of the Paris sewers connects to broad thematic sequences of corruption, concealment, and power politics. The second time through, you say to yourself, "Ah -- I see."

This "I get it now" response is a reward for rereading a book designed to be reread. One experiences it, not just in the dissertations, but also when one comes across certain exquisite plot foreshadowings. No reader could possibly identify or make sense of all of these foreshadowings on first reading. An example: Fantine, still a beautiful young girl unacquainted with tragedy, watches a horse being beaten to death on the streets of Paris. She herself, in time, will be beaten down by the city.

Conclusion: Even at half a million words or so, this book is designed to be read multiple times, and deserves multiple readings. Of course, this is a subjective conclusion. For me, the second reading was better than the first, and the third was better than the second. Only a writer, perhaps, can grasp the difficulty of creating such a book.

In particular, I found that the diversions were (amazing!) all manageable the second and third time through. They take the book out of conventional fiction mode and tie it to a much larger experience, a journey that reserves the right to make stops at countless minutiae of history, architecture, the progressive impulse, urban development, gender relations, sewer design and on and on -- the journey of LIFE. It's a little like having Jacob Bronowski serve as a collaborator and guest host on a month's episodes of ONE LIFE TO LIVE.

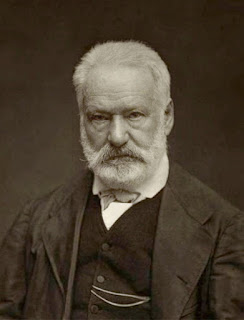

If ever a writer won the right to fold dissertations into his soap opera, it is Victor Hugo.

So what do we have? A book that never ends, and more than that, a hybrid that never ends.

I believe this book is designed to operate on at least three levels, only one of which (the first) shows up in the popular musical adaptation or in any other adaptation I've seen. The levels are:

1. The Drama (discussed above)

2. The Diversions (discussed above)

3. The First-Person Essays (discussed below)

These three worlds intersect to create, for patient readers, a single world of seemingly endless complexity and resonance. It's an illusion -- a literary trick -- but it's an astonishing effect.

Easier to miss than the drama and the diversions, which I've already examined briefly, is Hugo's careful, conscious decision to weave his own personal experience into the book. Let's look at those next.

The "I" essays give the appearance of being tucked into one of the other two compartments, and despite what I have called them they do not involve the first-person-singular "I" voice. Hugo achieves his multi-layered effect with a canny second-person "we" that fuses, in complex ways, with the book's editorial "we" -- and guess what that means? It means LES MIS is a personal journal, as well.

It is Hugo himself who tours the silent battlefield of Waterloo decades after the battle, and Hugo who shares his own personal memories of the barricades of 1832 as the insurrection raged in Paris.

These "I" reference-points are easy to miss the first time through because the reader is still off balance, trying to taking in larger episodes and/or rants. They become clearer, and more essential, on the second read. The "I" episodes are sometimes are very short. although the two instances I have given are lengthy ones. But they seem to me to present another conscious device: Hugo goes out of his way to establish and re-establish his own identity as an individual, though not as a character in the drama involving Jean-Valjean et al. You are never allowed to forget the author's literal presence in the story, and that presence increases in visibility and importance with repeated readings.

I've never read anything remotely like LES MISERABLES. It's a radical book, structurally, and I'm still not sure how he pulled it off. But I know these three worlds do exist, and I do know they cross-pollenate to create a variety of literary magnetism that's distinctive to this work.